August 20, 2005

By JOSHUA BROCKMAN

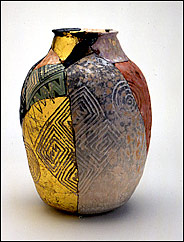

PHOENIX – Decorated with spirals and migration symbols, Nathan Begay’s multicolored jar resembles an ancient assemblage of shards. But it’s actually a synthesis of historical and modern: Mr. Begay, a 46-year-old artist of Hopi and Navajo descent, created it five years ago.

Its inclusion with some 2,000 other objects in the Heard Museum’s new exhibition of its permanent collection here reflects a sweeping change in the way museums are presenting Native American art. Rather than focusing on an ethnographic past, they are celebrating the full continuum of such art, juxtaposing contemporary pieces with historical ones and integrating native voices – often first-person narratives – into explanatory text and media.

From the Heard, to the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis, to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, museums with substantial Native American collections are aggressively pursuing new work.

To that end, dozens of museum officials will converge this weekend on Santa Fe, N.M., along with thousands of other private collectors, for the city’s annual Indian Market. The gathering, which began in 1922, draws more than a thousand Native American artists who sell their work and compete in a juried competition held by the Southwestern Indian Arts Association. Museums seize the opportunity to discover contemporary artists and to become directly acquainted with them.

Nathan Begay’s jar is a synthesis of historical and modern designs. Heard Museum.

Aside from its striking landscape, the Southwest continues to capture the public imagination because of the presence of Native American communities that keep their art, culture and language alive. The Heard’s proximity to those communities and its first-person approach has led to some curatorial insights.

“It all starts with a commitment to get it right in the eyes of our native advisers and native communities,” said Frank H. Goodyear Jr., director of the Heard. “We want to present the material in a way that connects to people and helps them understand native cultures, builds cultural sensitivity, builds cultural awareness, and makes them want to go beyond what they’ve seen.”

The museum’s installation, titled “Home: Native People in the Southwest,” opened in a refurbished 21,000 square-foot gallery in May. It was years in the making: the Heard’s previous permanent exhibition was in place for two decades.

In June, the Eiteljorg in Indianapolis also opened a reinstallation of some of its Native American collections, in a new 45,000-square-foot wing. The Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass., is developing a new installation as well. A common thread in these efforts is to display Native American holdings as full-fledged art objects, but with a heavy emphasis on process and context.

The installation at the Heard, displayed by tribal geography, covers the spectrum of peoples in the region. More than 50 recorded interviews with members of Native American tribes serve as the foundation for themes like homeland, language, family and community that are explored in exhibition text and presentations on electronic kiosks.

Pottery provides a natural introduction to the exhibition themes, since clay is gathered from homelands and a finished work serves not only as decoration and a means for carrying on aesthetic traditions, but also as a vessel for cooking and storing food and water. Nampeyo, whose pottery is on view, was the matriarch of a dynasty of Hopi-Tewa potters and artists: a 1976 jar with a butterfly motif by her great-granddaughter Dextra Quotskuyva is on display nearby.

Ms. Quotskuyva’s son, Dan Namingha, carries on the tradition as a painter; his “Red-Tailed Hawk Katsina” is one of the few paintings on view in the exhibition. “My mother’s work, the technical aspect is very traditional, but her ideas are contemporary in the sense that sometimes she’ll capture something that relates to her currently,” Mr. Namingha said in a telephone interview. “I’m the same way, and Nampeyo was the same way.”

In general, museums are distancing themselves from presenting Native American art through the lens of only one discipline like art history or anthropology, said Mr. Goodyear of the Heard.

A bracelet by Charles Loloma, from the “Home” exhibition. Heard Museum.

“Museums and native peoples have had a tenuous if not difficult relationship over the years,” he said, “and that relationship hasn’t been helped by the fact that the folks that have been traditionally interpreting the material have been non-native anthropologists, archaeologists, ethnographers, cultural historians and art historians.”

The Heard began breaking down some of these barriers in the 1980’s, Mr. Goodyear said, but today the hot issue remains, Who controls the material?

W. Richard West Jr., director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, said that his curators try “to emulate the original context as much as possible.”

“That’s why we have worked directly with communities, that’s why we have asked them to talk about the objects themselves,” he said, adding, “From the native standpoint, it was the process involved in the creation of an object that was far more important in the end than the object itself.”

The often densely packed objects and video histories in the Heard’s show make for a saturated sensory experience. In a video, Larry Brown, a San Carlos Apache, handles a circa-1900 hand-tanned buckskin saddlebag and explains that the cutout designs with red material underneath were peculiar to the Apaches. A Zuni jeweler, Dan Simplicio Jr., says in the text that much of the large-format Zuni jewelry was made to be worn in ceremonies by both participants and spectators so that it “could be could be seen by the ancestors looking down showing that people are well and surrounded with beautiful things.”

The bracelets, pendants and bolos of Jesse Monongya, a Navajo-Hopi artist who became a jeweler in the mid-1970’s after serving in Vietnam, figures prominently in a “Defending Home” section. Other objects in that area include a Navajo bracelet fashioned around a Purple Heart awarded in the 40’s.

Amid the debate over presentation, from videos to mounted objects to blending old and new, the distinction of “art versus artifact” remains an important issue, said Dan Monroe, director of the Peabody Essex Museum.

“Native American art was collected not as art, and not really even as artifact, but really as specimen,” he said. “That’s why the vast majority of art collected from indigenous cultures resides in natural history museums.

“The reason was that flora, fauna, and ‘primitive’ cultures all were conceived as being closely aligned. Certainly no one was talking or thinking about ‘native American art.’ That view held well into the 1930’s.”

At the Peabody Essex, “we like to make it clear that Native Americans are here and are still creating art, albeit in very different ways in some respects than they did in the past, which is precisely what one would expect,” he said, adding, “Cultures can’t exist and be static.”

Neither can museums, which is why the Heard’s “Home” exhibition includes room for change. By updating exhibitions, it aims to keep the public informed about contemporary Native American culture and counter stereotypes.

These days, plenty of contemporary works address those stereotypes head on, like the digital photographs in “Will Wilson: Auto Immune Response,” part of “Artspeak: New Voices in Contemporary Expression,” a show running through Sept. 30 at the Heard, and “Iconoclash,” continuing through Jan. 16 at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe.

In “Iconoclash,” Marcus Amerman’s “Something Wicked” depicts a train pulling cargo that includes Buffalo Bill, the Lone Ranger and Tonto, and the American flag, among other objects and personalities. In the foreground, buffalo are scattering in fear.

“The train is just American culture coming into this continent and all the things good, bad and strange it brings,” the artist said in an interview. David Bradley’s sculpture “Land O’Fakes” in the same show confronts fraud in the Indian art market and “the commodification of Indian culture – the packaging of it in an attractive way to make money,” as the artist puts it. It is not clear whether the Indian princess he depicts is a Native American or a white woman dressed in Indian clothing. The logo on the back of the sculpture reads “Land O’Bucks,” and the top mimics the packaging for “Land O’Lakes” butter. (The company is based in Minnesota, and Mr. Bradley is a Minnesota Chippewa.)

In his paintings, Mr. Bradley reinterprets popular imagery in a native context. His “To Sleep, Perchance to Dream,” for example, is modeled after Henri Rousseau’s “Sleeping Gypsy.”

“While the Indian is sleeping, his homeland is being turned into a huge tourist attraction – Hollywood on the Rio Grande,” the artist said.

Read original article, which appeared in Arts & Lesiure, Section A, on pgs. 15, 21.

© The New York Times Company