The writer kayaking near a rower on the Schuylkill in Philadelphia, by the Columbia Bridge.

Joyce Dopkeen for The New York Times.

October 18, 2013

By JOSHUA BROCKMAN

PHILADELPHIA — When rowers descend here next weekend for the Thomas Eakins Head of the Schuylkill Regatta, they’ll be racing in a riverscape brought to life in Eakins’s celebrated rowing paintings.

Eakins took great pride in his city, the backdrop for most of his life and work. In a letter from Paris in 1866, shortly after he arrived to study, he wrote that he felt “6 feet and 6 inches high” whenever he told Frenchmen about Philadelphia. He added: “Many young men after living here a short time do not like America. I am sure they have not known as I have the many reasonable enjoyments to be had there, the skating, the boating on our river, the beautiful walks in every direction.”

Eakins made his rowing pictures in Philadelphia between 1871 and 1874, and although he produced fewer than a dozen oils and watercolors on the theme, they are among his most popular paintings. “The Pair-Oared Shell,” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is the only one in this city. I’ve returned to see it dozens of times since my childhood, and it comes to mind whenever I’m paddling or rowing on any river, lake or ocean. The painting’s magnetic pull comes from its tangibly realistic rendering of two rowers in their shell passing under a bridge, bathed in early evening light.

A pier from an earlier version of the Columbia Bridge casts a shadow in Thomas Eakins’s painting “The Pair-Oared Shell.” The Philadelphia Museum of Art.

What drew Eakins to this scene and to rowing pictures? For some answers, I hit the Eakins trail, choosing a sea kayak to navigate a stretch of river known even today for its world-class rowers. (This year alone, the city is host to 44 regattas.) It’s also possible to explore on foot and bicycle via the Schuylkill River Trail.

The logical starting place to take a stroke in Eakins’s waters is Boathouse Row, in Fairmount Park, the nerve center of rowing. It’s where Eakins, an amateur rower, would have put in. (His family’s home, with a fourth-floor studio where he did most of his painting, is on Mount Vernon Street, within walking distance; it’s now home to the city’s Mural Arts Program, but the friendly staff has been known to give informal tours.)

I wanted to follow suit. Lloyd Hall, at 1 Boathouse Row, is advertised as “Philadelphia’s only public boathouse.” But when I ambled up to the river’s edge one recent afternoon, I found a dock with no gangplank; although some public-school groups and rowing classes put in at Lloyd Hall, it’s not the city’s recommended access point for solo boaters.

Thwarted, I headed to the nearby Undine Barge Club. Frank Furness was a principal architect of this boathouse, as he was for the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where Eakins taught and served as director. Outside, a young man was loading his 26-foot racing shell on top of his car as rush-hour traffic whizzed by. He was Charlie Biddle, 27, training for the United States national team, and after I shared my problem about where to put in — except for Lloyd Hall, the dozen or so boathouses on the Row are private — he invited me to kayak from the club on another day. Philadelphia, after all, is the city of brotherly love.

Eakins’s interest in painting rowing scenes may have emerged from his studies in Paris with Jean-Léon Gérôme, who painted oarsmen rowing on the Nile. The sport was also new in America, presenting a fresh subject for an artist eager to make his mark.

“He loved the subject of rowing,” said Kathleen Foster, senior curator of American art at the Philadelphia Museum. She added that Eakins also loved how rowing provided “beautiful bodies in the outdoors, and a huge opportunity for figure painting.”

To figure out how to render the long, slender racing shells in space, Eakins made the most detailed perspective drawings of his career.

“A boat is the hardest thing I know of to put into perspective,” Eakins told his art students. “It is so much like the human figure. There is something alive about it.”

Two large preparatory drawings for “The Pair-Oared Shell” (which can be viewed by appointment in the museum’s prints and drawings room) reveal how Eakins approached the shell — not just the rowers — as a portrait. One drawing positions the shell and oars on a checkerboard grid in relation to a pier from the Schuylkill’s Columbia Bridge. There’s even a shadow line on the bow of the boat that one scholar used to calculate the position of the sun and the time of day (around 7:20 p.m., in the early summer). The other drawing adds two rowers — and watercolor — in a mesmerizing study of how to render reflections in the ripples on the water.

On the appointed day, I launched from Undine’s dock into the brown waters of the Schuylkill (pronounced SCHOOL-kul). Mr. Biddle was in his racing shell, and I was taking my first strokes in the Focus, a new Wilderness Systems sea kayak designed for fitness paddling that the maker had sent me to test out. My mission was to paddle around three nearby bridges whose precursors featured prominently in Eakins’s work. (The locations are the same, the bridges have been updated.)

Another view of the Columbia Bridge. Joyce Dopkeen for The New York Times.

I immediately noticed how the kayak cuts through the water, moving more effortlessly than other, more traditional sea kayaks that I’ve paddled recently. The Focus is a 15-foot plastic boat — with ample hatch storage space for an overnight weekend trip — that weighs 50 pounds and is meant to be easy to carry, to load on a car and to store. The thigh and hip braces made for a snug fit in the cockpit, which gave me a boost and helped make my paddling strokes more efficient. The rudder was also handy for keeping me on course when the wind or current picked up, or when I was trying to chase Mr. Biddle, who typically rows up to 22 miles a day in a sleek white Italian racing shell with a blue stripe.

He introduced me to the rules of the river road that have been around since Eakins’s day. Head upstream on the west side and downstream on the east. This is especially important, since rowers face backward and kayakers forward: you want to avoid a jousting match with a high school shell powered by eight rowers and a coxswain.

Our first stop was the Girard Avenue Bridge and the adjacent Connecting Railroad Bridge. The river scene (looking south, downstream) served as the backdrop for Eakins’s first finished work in the series: “The Champion Single Sculls.” It’s a portrait of Eakins’s high school friend Max Schmitt, who had won a single-scull competition in October 1870, and it includes a self-portrait of Eakins rowing. The painting is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. As an Amtrak train heading south from New York rumbled over the stone masonry arch bridge, I paused to watch a merganser dive into the dark waters.

The New York Times

Continuing upstream, rounding a sharp bend in the river, I saw the Columbia Bridge looming, hawks circling above. This setting (the current bridge was built in the 1920s) captured Eakins’s eye; one pier of the previous bridge figures prominently in “The Pair-Oared Shell.”

Eakins’s friends the brothers John and Barney Biglin were the professional rowers in that painting, and Mr. Biddle offered the best explanation for their focused posture as he talked about racing. “You’re really kind of oriented to your task,” he said. “You have to pay attention to all these things you can’t see.”

In the midafternoon, I had the bridge practically to myself, and I couldn’t help paddling figure eights through the piers and their reflections and shadows. Before heading back downstream, I looked through the bridge and across to the west bank, where a green swath of trees dominates the view — just as it does in the painting. At that moment, I recalled what Elizabeth Milroy, an expert on Fairmount Park at the Philadelphia Museum, told me: “Once you’re on the river, there’s no city.”

I floated in the waters, watching various rowers pass momentarily through the darkness into sparkling light. Eakins captured moments like these in his paintings: the light, the water, the shell, the rowers and the park. It’s all still here in Philadelphia. You can find it on the river.

How to Roll on the River

PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway; (215) 763-8100, philamuseum.org.

PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS 118 and 128 North Broad Street; (215) 972-7600, pafa.org. The academy and the Philadelphia Museum together have the largest holdings of Eakins work in this country.

THOMAS EAKINS HOME 1729 Mount Vernon Street; (215) 685-0750, muralarts.org.

BOATHOUSE ROW The Schuylkill Navy posts information on all regattas in Philadelphia, as well as safety information and rules; boathouserow.org.

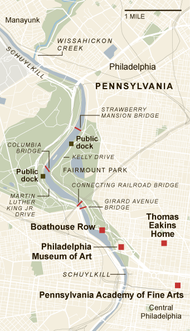

PUBLIC DOCKS There is supposed to be a public gangway at Lloyd Hall on Boathouse Row, but the Parks Department recommends the dock just south of Columbia Bridge on Martin Luther King Jr. Drive for weekdays, and the dock south of Strawberry Mansion Bridge on Kelly Drive for weekends; phila.gov/parksandrecreation.

BOATS Wilderness Systems’ Focus, the kayak I tested, retails for $1,639; wildernesssytems.com. There are no boat rentals on this section of the river. Eastern Mountain Sports, at 525 West Lancaster Avenue, in Haverford, is the closest outfitter for kayaks ($50 a day includes boat, life jackets, paddle and roof ties with foam blocks); (610) 520-8000.

MAPS AND CONDITIONS schuylkillriver.org; phillyrivercast.org.

MORE INFORMATION Budget at least one and a half hours for the three-mile round-trip paddle from Columbia Bridge to Boathouse Row. Stay close to the east bank when approaching the Row, as there is a low-head dam just downstream, an extreme hazard. For a longer, seven-mile round-trip excursion to see other bridges that Eakins studied, head north from Columbia Bridge to Manayunk. Tie up at the Manayunk Brewing Company’s dock, about a mile north of the Philadelphia Canoe Club, at the confluence of Wissahickon Creek and the Schuylkill, for a lunch break. Manayunk Brewing Company, 4120 Main Street; (215) 482-8220. JOSHUA BROCKMAN

Read original article, which appeared in Weekend Arts on p. C31.

© The New York Times Company