Room with a view: A group of sea lions takes a break from feeding in the vicinity of a natural arch on Santiago Island. ©Joshua Brockman 2007. All Rights Reserved.

By Joshua Brockman

Standing knee-deep in translucent water, my feet planted in the coral sand, I watch dozens of great frigate birds circling overhead. Several sea lions snooze on the beach behind me. Their sleek chocolate-brown bodies, tucked between the gray sand and the black volcanic rock, resemble Henry Moore sculptures.

The tropical waves gently roll into this protected cove. But the flow is interrupted when a shredded white plastic bag washes against my leg like an unwelcome jellyfish.

In the beginning there were just animals here and no people. As I pick up this trash, I recall reading rule number one of the Galápagos National Park, printed on the back of the customs form: “Cause the least possible impact on the islands. Take only photographs, leave only footprints.”

In the late 1960s, when tourists first started to trickle in to explore the islands aboard tour boats, the human footprint wasn’t a big part of the equation, because there were fewer tourists and locals. But over the years both constituencies have grown, transforming the sparsely populated outposts into towns with a quiver of urban problems.

Tourism. The Galápagos have dined off it for forty years. Now the people of these islands realize, like so many places, that they have to create a new kind of sustainability or risk killing off the very things the tourists come to see.

Heading South

I’ve come to the Paris of eco-tourism, six hundred miles off the coast of Ecuador, to plumb the vital issues facing the islands, including tourism, energy, conservation, invasive species, population growth, water, and waste. All of these are deeply interwoven in this archipelago, where ecosystems—and the islands’ very identity—hang in the balance.

All eyes are focused on the Galápagos, as if another volcano were about to erupt, to see what new tourism model will emerge to replace one that is four decades old. The stakes are high. The new model will likely reduce the number of tourists permitted to visit the archipelago each year, require longer stays, and boost local ownership of and participation in tourism ventures.

I’ve joined an international “A team” of experts from the public and private sectors, including the new governor of the Galápagos, Eliecer Cruz; the executive director of the Charles Darwin Research Foundation, Graham Watkins; the managing director for the World Wildlife Fund’s Galápagos program, Lauren Spurrier; Santiago Dunn, the president of Ecoventura, an Ecuadoran cruise outfitter in the Galápagos; and Bill Reinert, the “godfather” of the Prius and the national manager for Toyota’s advanced technology group.

Over the course of four days, we’ll cruise aboard Ecoventura’s Flamingo I, an eighty-three-foot yacht, zip along the shoreline in Zodiacs, hike on trails, and snorkel and kayak in the archipelago’s tropical waters. Our floating think tank will visit seven major islands: Baltra, Genovesa, Fernandina, Isabela, Santiago, Bartolomé, and Santa Cruz. Afterwards, we’ll visit the town of Puerto Ayora, the tourism hub of the Galápagos.

In 2006, more than 145,000 people visited the islands, up from 40,000 in 1990. This sizable uptick in traffic threatens the very creatures and ecosystems that are the star attractions of the Galápagos.

Last April, the president of Ecuador, Rafael Correa, pledged to make the Galápagos the main focus of his government’s environmental agenda. UNESCO followed by placing the Galápagos on its World Heritage in Danger list. (Back in 1978, the archipelago had become the first place to be named a World Heritage site.)

During my thirty-six-hour journey south, it was like riding in a high-altitude library. Two dozen books were passed around. My seat companions offered me a choice of two classics: Darwin’s Finches and Galápagos: A Natural History. While others slept from Miami to Guayaquil, travelers heading to the Galápagos had their reading lights on. Mine was focused on Darwin’s Enchanted Isles. We were on a pilgrimage to the land of Darwin.

Baltra (Energy)

Not far from the Baltra airport, abandoned ammunition bunkers and an old officers’ club dot the landscape—vestiges of World War II, when the U.S. military set up an air base to protect the Panama Canal. After the war, the military walked away, leaving behind oil and fuel facilities that were built to last only a few years.

The Galápagos, like most island communities, is locked in a diesel fuel dilemma. The power plants on Santa Cruz and throughout the archipelago still use old diesel generators to produce electricity, in a highly polluting process. All cruise boats are also dependent on diesel.

In 2001, when the MV Jessica spilled 150,000 gallons of oil off the easternmost island, San Cristóbal, it served as a wake-up call for the local community and for conservationists. The World Wildlife Fund recruited Toyota to assist with developing a sustainable energy plan for the archipelago. After examining the movement of fossil fuels and how they were being utilized in the islands, the team determined that the most significant pollution threat to the archipelago was the Baltra fuel terminal—the facility where all diesel and gasoline enters the archipelago and where it leaves on cruise ships destined for other islands.

Advanced oil: A slop tank in Baltra’s high-tech fuel terminal removes saltwater contamination from fuels as they enter the island, helping to stem engine pollution throughout the archipelago. ©Joshua Brockman 2007. All Rights Reserved.

More than fifty years after the war, dilapidated tanks were still in use, without any environmental protection systems to contain spills.

“For all practical purposes, in the United States, it would have been a Superfund site,” says Spurrier, a Peace Corps alum, recalling how fuel used to leak all over the place. Reinert, a lanky engineer, whips out a laptop to show me photographs of sea lions hanging out in pools of diesel and tanks corroded by the salt water.

Five years ago, most of the oil and gasoline arriving in the Galápagos was contaminated with seawater. After delivering their fuel, tankers return to the mainland empty. To compensate for their lighter weight, they typically flood their fuel tanks with seawater as ballast to give them a more stable ride. Inevitably, some salt water remains in the tanks, which contaminates the fuel, but a new system solves that problem.

The harbor is now home to a high-tech Baltra fuel terminal with automated fuel-transfer and fire-protection systems. It even has its own “slop” tank to remove saltwater contamination from different fuels as they enter the island. All of the more than eighty boats with permits to take tourists on cruises in the Galápagos must come here to refuel.

“As it sits today, it’s the most advanced oil depot certainly of any island community in the world and probably more advanced than any oil facility in Latin America,” says Reinert, burying himself inside the circuitry of one of the control rooms.

The quality of fuel has a trickle-down effect on the entire archipelago, especially when it comes to pollution. Dunn takes me out to the Flamingo I, past nearly twenty cruise boats anchored in Baltra Harbor, in a Zodiac powered by a four-stroke motor with separate oil and gas systems. Previously, the low-quality fuel meant that all fishing boats and Zodiacs had to rely on two-stroke motors that ran on a mixture of gas and oil and discharged oil into the ocean through their exhaust.

The transformation of the fuel terminal is emblematic of the substantial makeover under way in the Galápagos. The changing of the guard, with a new governor in office, and with experienced directors at the helm of the Galápagos National Park and INGALA (Galápagos National Institute, the agency charged with handling migration issues), means that the archipelago is in a unique position to update everything from its forty-year-old tourism model to its recycling practices.

“For the first time in Galápagos, we really have a clear and very big opportunity to make a change. That doesn’t come around twice,” says Watkins, a stocky zoologist whose voice resembles that of actor Patrick McGoohan, and who worked as an official guide in the Galápagos in the late 1980s.

Genovesa (Invasive species)

Early Monday morning on the Darwin Bay trail, we gather like a pack of paparazzi around two swallow-tailed gulls watching over their newborn fur ball. I expect them to scatter like pigeons, but they just ignore us like the thousands of other seabirds do.

Two stylish Nazca boobies at home on Genovesa Island. ©Joshua Brockman 2007. All Rights Reserved.

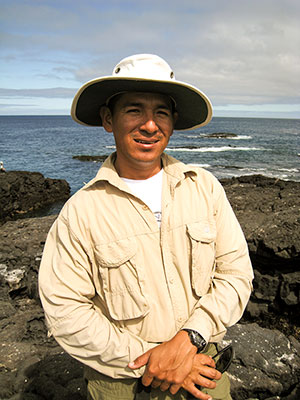

All tourists must travel with guides, and our Galápagos National Park chaperone for the next four days, Harry Jiménez Jhonjones, has been one of the park’s guardians for twelve years.

Governor Cruz squats down with boyish enthusiasm and snaps some images of the chick as it flaps its wings. Behind a nearby rock, there’s a dead blue-footed booby in the sand. A corpse and a baby—there’s a continuous cycle of life and death on display among the rocks and mangroves.

“It’s fascinating that all the animals are so tranquilo,” I tell Harry.

“That’s Galápagos,” he replies.

Cruz leans in and says: “Tranquilo is no competition.”

It’s also tranquilo on Genovesa because this island has had no exposure to invasive plants or mammals. At fifty thousand square miles, nearly the size of Louisiana, the Galápagos Marine Reserve is the second-largest marine reserve in the world, after Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Despite the islands’ isolation and the vast area, the archipelago is quite susceptible to invasive species.

In Guayaquil’s modern airport, I encountered the first security perimeter as I placed my luggage on a conveyer belt for a biological scan that’s part of the quarantine-and-inspection system designed to protect the ecosystem from pests and diseases.

Red-footed boobies model and preen on Genovesa Island. ©Joshua Brockman 2007. All Rights Reserved.

Then, in midair, just as Santa Cruz Island popped into sight, the flight attendants opened all of the overhead luggage compartments. The P.A. crackled and there was a mumbled statement about the World Health Organization sanctioning this new procedure. A flight attendant passed by, spraying an insecticide into the overhead bins as another closed the doors behind her just in time for our landing. For the first time, I was grateful not to have an aisle seat. As the acrid smell filled the cabin, my eyes and throat started to burn. Welcome to the Galápagos in the age of the West Nile virus.

But these precautions aren’t enough. Tour operators like Dunn have to fly in all of their food for each trip they run. And cargo ships are constantly sailing back and forth from the mainland transporting perishables and thousands of other items in cardboard boxes that can play host to unwanted hitchhiker seeds, insects, or other organisms. The ease with which organisms can move from one island to another became clear when I boarded a six-passenger airplane to travel from Baltra to Isabela and a stowaway fly buzzed into the cabin.

Lindblad Expeditions is testing a system for pre-processing and vacuum-packing all of its food so that no introduced species travel with it to the archipelago.

“It only becomes meaningful if we can develop a system to share with others,” says founder Sven-Olof Lindblad, describing the company’s plan to make the packing system viable for all tour companies and grocery stores in the archipelago. For the Galápagos to become a sustainable island culture, best practices have to be shared.

The problem is widespread in Santa Cruz Island’s agricultural zone, where horses are tethered to trees or fences on the side of the road but invasive plant species—including banana, hibiscus, guava, teak, quinine, papaya, mango, and palm—are running wild.

“The agricultural areas are actually the most damaged areas of the Galápagos,” says Watkins.

Cruz is dressed for a day at the “office” with his Patagonia fleece vest, Keen sandals, and mirrored sunglasses sitting atop his closely cropped head of graying hair.

Governor Eliecer Cruz visits his “constituents” on Genovesa Island. ©Joshua Brockman 2007. All Rights Reserved.

We walk together, listening closely to Harry, but Cruz could be the one giving the talk. At the age of 29, he assumed the top job in the park and served as its director for eight years. The World Wildlife Fund then hired him to be their man in the Galápagos. Four months ago, President Correa called and he became governor.

At every turn, Cruz clicks away with his camera, capturing images of a red-footed booby sitting on an egg in its nest, a brown pelican in a tide pool, a juvenile frigate bird in a mangrove.

“In terms of conservation, we can say that the islands are much better conserved today than they were thirty years ago,” he says as we walk along a sandy plain filled with palm-size rocks. “However, in terms of potential threats and potential impact, the islands are much more threatened today.”

Harry chimes in suddenly. “Careful, careful, watch out,” he says, squatting down and spreading his arms in front of us. We nearly step on two small sea lions sleeping on the sand. They’re perfectly camouflaged, interspersed with the rocks like wet driftwood.

Before we leave Genovesa, Cruz and I hop into a sea kayak to explore the bay and to visit more of his constituents—the hundreds of thousands of seabirds. A native son of the Galápagos, Cruz grew up on the tiny island of Floreana, the tenth of twelve children—all delivered by his father.

As we paddle closer to the cliffs to explore some sea caves, a red-billed tropic bird gusts over our kayak, and Cruz is quick to identify it for me. It’s second nature for him, with his degrees in biology and environmental management. His scientific and technical background has galvanized the community, because it signals a shift away from politics as usual. No one—including the president of Ecuador—seems to care that he has no background in politics.

Cruz tries to steer the kayak from the bow. Things are a bit wobbly as we ride the waves, taking on a little water. It takes some time before we’re balanced. As governor, the balancing act Cruz hopes to achieve includes managing tourism and development, conserving wildlife and ecosystems, and preventing the arrival of introduced species. It’s a tall order.

“Where are you taking me to, Puerto Ayora?” Cruz jokes as I turn the kayak back toward the Flamingo.

Down on the Iguana Deck—where I’m in a cabin across from Cruz—it’s a long and sleepless night. It turns out that “Iguana” is a fancy word for “forecastle”—the engine churns continuously during our 125-mile voyage to the western edge of the park.

Fernandina (Conservation)

It’s low tide as we approach Fernandina—a thin layer of black pahoehoe lava and a thick layer of green mangroves sandwiched between expansive ocean and sky.

Because this island is so well preserved, the tide pools resemble gardens for endemic species. The green algae on the surface of the smooth volcanic rock stands out like a lawn of grass, with red Sally Lightfoot crabs scurrying about. As we walk, the air begins to smell of excrement. On the rocks and in the water, I’m surrounded by small Godzillas—hundreds of marine iguanas basking in the sun and feeding on algae in all of their prehistoric glory. Nearby, a flightless cormorant stands upright.

Marine iguanas embrace a piece of driftwood on Fernandina Island. ©Joshua Brockman 2007. All Rights Reserved.

Fernandina is the poster child for conservation, largely because it is one of the uninhabited islands in the archipelago. It’s also a foreign land for some of the Galápagos’ residents.

“Many kids that live in the town here [Puerto Ayora] have never even actually seen the Galápagos that tourists see,” says Watkins. Without exposure to the biodiversity, living in the park or on its edges has no meaning. The vast majority of land—97 percent—in the archipelago is part of the national park. People live in the other 3 percent.

Education is closely intertwined with conservation, and efforts are intensifying to give children who grow up in the Galápagos an understanding of social ecology—the relationship between themselves and the environment. When coupled with vocational training, which enables locals to be employed and to benefit from tourism and its associated businesses, this effort creates what Watkins describes as an island culture—“a culture of people that understand what it is to live in islands, the restrictions, the difficulties of business development in islands and how to make it truly sustainable.”

While the word pristine is often used to describe this island and much of the Galápagos, tourism—no matter how carefully it is monitored and enforced—has its impacts. Some direct impacts are obvious, such as the wear and tear on walking trails on the islands. As a living ecosystem, the park has to be managed with a flexible system where sites are periodically closed to give areas rest or recovery time.

Sadly, tourists are part of a system that does not operate with a leave-no-trace ethic. Their indirect impacts may be the most harmful—like when goods and services are carried in to enrich their experience but the waste and by-products are not necessarily carried out when they leave.

As I’m walking with the governor, we pass an algae-encrusted engine wheel and a driveshaft from an old steamship. It’s a reminder that human debris and mistakes—like the 2001 Jessica oil spill—can have a long afterlife.

When we return to the Flamingo, there’s a fishing boat, Paraiso—“Paradise”—anchored nearby with a sign that all boats in the Galápagos must post: no botar basura al mar—“Don’t throw trash into the ocean.”

“Who wants fresh lobster for dinner?” Dunn asks as he jumps into a Zodiac, grabbing Cruz, Harry, and me as his away team. We scramble onto the deck of Paraiso and shake hands with Captain Hector and his crew of 14. Everyone recognizes Cruz, but there’s no red carpet for him: they know him as a fellow galapageño. And although there’s no gubernatorial discount, Cruz and Dunn negotiate a deal, and for $71—along with some recent newspapers, Coca-Cola, water, and fresh vegetables—we leave with more than a dozen slipper lobsters and some grouper for dinner.

Slide Show: A Tour of Galápagos

[rev_slider Galapagos]

Isabela (Water)

A bird’s-eye view of Isabela Island. ©Joshua Brockman 2007. All Rights Reserved.

We cross the Bolívar Canal to Tagus Cove, on Isabela—the largest island in the Galápagos, where Galápagos penguins are sunbathing beneath a large display of graffiti. The year 1836 is carved in the rock—just one year after Darwin arrived aboard the Beagle to visit this island. As we hike up flights of stairs, past silvery palo santo trees, we arrive at an overlook with a view of Darwin’s lake.

Harry tells us that when Darwin saw this lake, he ran down to it thinking he had found freshwater, only to discover that the water was saltier than the ocean.

Freshwater is scarce in the archipelago. The main source of water is volcanic cracks that run through the islands. But the water is brackish. For drinking water, people consume purified bottled water produced largely in the Galápagos. About 5 percent of drinking water is brought in from the mainland, at a very high cost.

In Puerto Ayora, when I checked into my hotel I was given the key and a gallon of purified water. The town’s water source is 100 feet belowground in one of many interconnected cracks. The brackish water is pumped up through pipes and into people’s homes. There’s one problem: most homes have no sewage system, so the water source has become highly contaminated with E. coli.

Captain of the ship: A sea lion commandeers a fishing boat on Isabela Island. ©Joshua Brockman 2007. All Rights Reserved.

Intestinal disorders and skin infections are common. Some locals head to the ocean to bathe in the salt water to avoid exposure. Others have installed water filters in their homes, and a handful of hotels have followed suit.

Despite the high-tech solutions in place for handling fuel and gasoline, the islands have no sewage treatment plant. The only one operating in the Galápagos is at Puerto Ayora’s high-end Finch Bay Eco Hotel.

Santiago (Population)

As we approach Puerto Egas in a Zodiac, I can see the skeleton of a cinder-block house. It has a million-dollar view, perched above the harbor named for Dario Egas, who ran a salt business here in the 1960s. To woo workers, he promised each of them a house, but no others were ever built.

New homes are sprouting up all over Las Cascadas, the poorest neighborhood in Puerto Ayora. The Galápagos have become a magnet for people from the mainland. The tourism-fueled economy has created jobs with better pay, and the lifestyle on the archipelago is tranquil. But not everyone is flocking here for a piece of the tourism pie—some come to take cleaning or agricultural jobs that Galápagos residents no longer want.

The population in the Galápagos is growing by 8 percent a year—three times faster than on the mainland. It has swelled to 28,000 people, with the majority—15,000—in Puerto Ayora. This includes nearly 3,500 people who are not registered as Galápagos residents.

As Cruz and I take a seat in his “office” on the volcanic rocks, he tells me he is most concerned about managing the growth in the local population. Any increase in population requires more housing and food, and that boosts the risk of having another oil spill as cargo boats carry supplies to and from the archipelago. It also translates into a far greater risk of introduced species finding their way to the islands.

Galápagos National Park guide Harry Jiménez Jhonjones basks in the glow of Santiago Island. ©Joshua Brockman 2007. All Rights Reserved.

Regardless of whether the population shrinks or grows, people are part of the ecosystem. Even though the human footprint is limited geographically to just 3 percent of the archipelago, local municipalities are overwhelmed by the need to provide even the most basic services.

One of the stumbling blocks is that there are far too many chefs in the kitchen.

The INGALA Council, which the governor heads, is the primary decision-making body for the Galápagos, but Santa Cruz is home to nearly 160 organizations that claim a stake in the future of the Galápagos. At least eighty are government institutions, and the rest include conservation organizations, both NGOs and private groups. It’s unmanageable. Watkins says it’s time to bring in the M.B.A.s and urban planners to help simplify and coordinate things. Otherwise the institutional framework will continue to dilute any vision for a sustainable Galápagos.

“That’s the key to Galápagos: having almost the single-mindedness to go in the direction of sustainability,” says Watkins.

Even though it was enacted a decade ago, many provisions of the Special Law for the Galápagos, a comprehensive legislative agenda designed to ensure conservation and sustainable development, were not implemented, because some of the institutions weren’t strong enough to enforce them. That’s also starting to change, especially with regard to curbing population growth. During the week of my visit, INGALA hand-delivered get-out-of-town notices to sixteen people in Puerto Ayora.

Bartolomé (Tourism)

During our last afternoon aboard the Flamingo, we arrive at one of the most photographed sites in the Galápagos, on Bartolomé Island. The 2 p.m. heat makes me want to cool off in the water. I snorkel past moray eels, parrotfish, and ridges of ancient lava, catching up to the governor as he’s swimming in the shadow of Pinnacle Rock.

Two pangas filled with tourists stop near the rock to observe a group of boobies. As we swim away, a large sea turtle flaps by. Seconds later, I turn around and see the back half of a sixteen-foot whitetip reef shark as it disappears into the murky water.

It’s a Galápagos moment.

Tourism is the main economic driver of the Galápagos. But the tourism model is forty years old. Of the $418 million that Galápagos tourism generates each year, only an estimated $63 million goes into the local economy. For sustainable tourism to exist, the model of tourism needs to shift toward a system that is driven by local, not global, market forces.

Every tour operator needs a concession license to operate in the park. Prior to the passage of the Special Law for the Galápagos, which requires at least a partnership with a local person, licenses were often granted to a person or company outside of the Galápagos, without any time limitations. The park is now reviewing a plan whereby concessions would be reallocated and distributed for a shorter period.

“We have to continue to ensure that tourism is implemented in a sustainable way and that tourism continues to finance conservation. We also have to work to ensure that the local population receives greater benefits from tourism,“ Cruz says.

He estimates that 30 percent of the permits for tour boats are in local hands, 50 percent are controlled by businesses in mainland Ecuador, and international tour operators hold 20 percent.

“The people who are benefiting from Galápagos are not the people who live here,” says Raquel Molina, the director of the Galápagos National Park. It’s causing a feeling of malestar, or uneasiness, among the local population. The plan, she says, is to break the current cycle, in which most of the benefits are going to a few people, and open up opportunities for the larger community.

Raquel Molina, the director of Galápagos National Park, stands in front of a mural at park headquarters that says, “There is still time to protect the Galápagos.” ©Joshua Brockman 2007. All Rights Reserved.

While tourism is the largest industry and the largest employer in the archipelago, 60 percent of people are employed in secondary businesses that support the tourism industry, such as fixing motors and driving buses or taxis.

Cruz is not alone in wanting to ensure that the Galápagos doesn’t become a haven for what he calls “mass tourism,” where visitors come to the archipelago for quick jaunts just to check the Galápagos off their vacation bucket list. By encouraging longer, two-week visits, the Galápagos could reduce the number of tourists by 40 percent a year and also attract those tourists most interested in wildlife and biodiversity, he says.

“Ecuador and Galápagos need to think about a more exclusive niche in the market, attracting people who really want to come to see the wildlife and appreciate the wildlife and are willing to pay for that experience,” says Spurrier.

Increasing the number of days a person stays won’t necessarily reduce human impact, however. And requiring longer stays also could shut the door on a younger generation of eco-tourists, who may not have the resources to finance a longer stay.

Santa Cruz (Waste)

The next day, I’m in Puerto Ayora visiting Leopoldo Bucheli Mora, the mayor of Santa Cruz, who is seated in front of the flags of Ecuador and Galápagos and alongside a bronze sculpture of a giant tortoise. Mora, a former nightclub owner, tells me that he would like to raise the cover charge—the entrance fee tourists pay to come to the Galápagos, which is collected by the national park—to $1,000 per person.

When would you like this to take effect?

“Ya,” he answers—right now.

Mora explains that Santa Cruz—along with the other two municipalities in the Galápagos, on Isabela and San Cristóbal islands—want “more selective” tourism coming to the islands. The $100 flat fee that I paid to enter is part of the reason so many tourists come, he says.

“I feel a lot of pressure, because Santa Cruz is the main point of entrance for tourism,” he explains. The municipality is struggling to provide basic services to citizens, including water, electricity, and a safe way to dispose of, collect, and manage garbage and recycling. What’s more, estimates suggest that trash on the island is growing at an astronomical rate—8 percent a year, commensurate with the population growth.

New construction is booming in Las Cascadas, one of the poorest neighborhoods in Puerto Ayora, Santa Cruz Island. ©Joshua Brockman 2007. All Rights Reserved.

In some countries, the face of the president or monarch is omnipresent, with framed portraits appearing on the walls of hotels, barbershops, and restaurants. In Puerto Ayora, a regular citizen named Don Parejita—who has worked for the municipality for decades, cleaning up the streets—enjoys this honor. His caricature—in a baseball cap, holding a broom and giving a thumbs-up—is plastered on or above nearly every trash and recycling can, as well as a giant billboard welcoming visitors with the slogan la basura sirve santa cruz limpia—“Recycling is working in Santa Cruz.”

More than a third of all the waste on the island, or about sixty-five tons each month, is recycled at the processing center in Puerto Ayora. Municipal workers sort the refuse each day near a mountain of collapsed cardboard boxes. Some ships have begun to bring their tourists here to better understand the journey of waste.

Relugal, an oil-recycling project that started in 2000 in Puerto Ayora, has already recycled 250,000 gallons of oil. Previously, fishermen and other boat operators had no way to dispose of their oil, so they would just drain it directly into the ecosystem—the ocean or the ground. Tour boats are now required to recycle their oil, which is then shipped back to Ecuador and used as a fuel source in a cement factory.

“There’s a lot of economic incentive to bring things onto islands, but there’s almost no economic incentive to take things off islands,” says Reinert, who helped set up this program in the Galápagos as a prototype for other island ecosystems.

Tourist impact: A dinghy picks up trash and recycling from yachts moored in Academy Bay in Puerto Ayora, Santa Cruz Island. ©Joshua Brockman 2007. All Rights Reserved.

Nineteen miles north of Puerto Ayora, smoke rises from an arid landscape filled with palo santo trees. From a distance, it looks as if a dormant volcano is acting up. The source is the island’s landfill, where a heaping pile of trash is burning. It’s an antiquated practice, but one used on many islands to reduce the volume of waste.

As a bulldozer moves back and forth, leveling the earth on the ten-acre plot, I spot a group of yellow warblers prancing around metal cans, tires, and scrap metal. Colorful striped plastic bags dot the landscape—the same ones dispensed by stores in Puerto Ayora.

Amigas Siempre

I sign out of Puerto Ayora and register for my visit to Tortuga Bay Beach by scribbling my name in the oversize registry book at the Galápagos National Park gatehouse.

Tortuga unfolds across the horizon like a giant white crescent. My feet sink into the cool white sand, deposited over millions of years from coral passing through the digestive tracts of parrotfish. My brief visit, like those of the thousands of other tourists who descend on the Galápagos each year, pales in comparison. Our footsteps will disappear when the tide rises. But our impact—intended or not—may be everlasting.

“The Protection of Galápagos Depends on You,” reads a weathered sign designating the nesting zone of marine turtles. Just around the bend, a trail leads me through mangroves and opens onto an inlet that locals call Playa Mansa (“calm beach”). The water is as still as a lake. Several small fish burst out of the water like an explosion of small firecrackers, driven by the pursuit of whitetip reef sharks.

I walk into a stand of opuntia cactus. Some of them are hundreds of years old, judging from their thick trunks. Their silhouettes stand out as the evening sun backlights their pads and spines.

“Omigas Siempre”—“Friends Forever”—is carved into the cactus. It’s misspelled and engraved for the life of the cactus, along with a few names.

A misspelled missive—promising “friends forever”— is engraved on an opuntia cactus near Playa Mansa, Santa Cruz Island. The lifespan of these plants can extend for hundreds of years. ©Joshua Brockman 2007. All Rights Reserved.

I hustle back along the crescent, which looks electric. The sand and the surf unite, joined by a glowing strip of orange water. There’s no sign of Puerto Ayora, just the Highlands on the horizon.

There’s something about the air in the Highlands, among the scalesia forests, that invites deep breaths. The magic is induced in part by the movement of the garúa—a whispy and transparent slice of cloud that mists and occasionally drops a light rain on the Highlands. Lichens and mosses coat the trees and dangle like soft brown and purple ornaments blowing in the wind. The sea lions aren’t barking, but this ecology is equally engaging.

I’ve come here with Watkins to hike around two volcanic sinkholes called Los Gemelos—the twins. It feels as if we’ve entered a landscape from a Japanese woodcut. Each scalesia, with its delicate branches and pointed leaves, stands alone like a bonsai. But under the collective green canopy, the forest comes to life. Watkins points out at least four species of Darwin’s finches, and when we emerge, a Galápagos dove flies over the sinkhole, disappearing into the garúa.

Back in town, I seek out Fausto Llerena near a cluster of baby tortoises at the Charles Darwin Research Station’s tortoise center. Llerena has been the caretaker for tortoises in the center’s breeding program for thirty-four years. He whisks me up a boardwalk to see Lonesome George, the last surviving Pinta Island giant. Then we enter a different giant tortoise pen—one that is open to the public.

Llerena wouldn’t normally be here on a Sunday morning. But he’s on patrol, keeping his eye on tourists.

“Some use them as horses and sit on them or stand on them,” he says. “They are very strong animals and they are very resistant, but if you have hundreds of people doing that every day, they’re obviously going to have an increased stress level and possibly die.”

Share the road: A giant tortoise in his lane near Rancho Primicias, Santa Cruz Island. ©Joshua Brockman 2007. All Rights Reserved.

I decide to visit the wild giant tortoises in the Highlands. Watkins accompanies me, and in the space of a few minutes we’ve gone from the Eden neighborhood to the outskirts of town, where a pink heart-shaped sign advertises Puerto Ayora’s brothel. The trappings of town quickly transition into farmland.

Not long after turning down a dirt road, we find giant tortoises huffing it along the roadside, powered by their elephantine legs. As the road narrows, we pull over to let tour buses by. At Rancho Primicias, we walk right into a field where there are dozens of giant tortoises. I squat down close to one of the males to take his photo. The sound of his breathing makes me feel as if I’m next to Darth Vader.

Watkins and I hear groaning. I wonder if a tourist is hurt. We move toward the sound, walking through taller grasses and weeds.

“Tortoise sex. That’s what was making the noise,” Watkins laughs, pointing to the angled couple. “She’s kind of caught there between a rock and a hard place.”

There’s a future in the Galápagos.

© Joshua Brockman 2008. All Rights Reserved.