August 22, 2002

By JOSHUA BROCKMAN

SANTA FE, N.M., Aug. 21 — Before daybreak Saturday morning, collectors who had pulled all-nighters in the booths assigned to their favorite artists were sprawled out in lawn chairs or cots, holding their place in line at this year’s Indian Market. Some had waited a day and a half.

The Indian Market takes its name from two intense days of selling Indian art at outdoor booths around this city’s plaza, but it has blossomed into a weeklong celebration of Indian culture with museum exhibitions, benefit auctions, gallery openings, music and even a film festival.

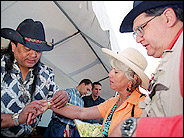

Jesse Monongye, a jeweler at the Indian Market in Sante Fe, N.M., shows a bracelet to Catherine Wygant and her husband, Dan Monroe. Cary Herz for The New York Times.

Indian Market, which began in 1922, is produced by the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts and attracts nearly 80,000 visitors, who spend millions of dollars. For many Indian artists the income from these two days, whether through sales or commissions placed at the market, sustains them throughout the year.

“This is a great launching for any Native American who wants to get discovered and noticed,” said Nancy Youngblood, 46, from the Santa Clara Pueblo, who is famous for her melon-shaped pottery adorned with elegant S-swirl rib designs. “The toughest competition is at this show.”

Artists are subjected to a rigorous screening process by the market’s organizers, and hundreds of them were kept out this year. With the current vogue for all things turquoise, the tourists and collectors who lined the streets last weekend could shop with confidence that all the materials and methods used were authentic. In addition to the usual browsers, there was a large contingent of museum directors and curators from the United States and abroad, many of whom are re-examining how they acquire and display Indian art. The concentration of more than a thousand Indian artists here, and the increasing number of gallery openings, has made Indian Market into an annual pilgrimage for a roster of museums.

“Museums that are not looking at this as a source of collecting are really missing the boat,” said Ellen Napiura Taubman, a guest curator at the American Craft Museum in Manhattan for its show “Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation,” which examines contemporary Indian art from the Southwest. “You can no longer put Indian art off to the side. I think it has just gotten too good.” Ms. Taubman, who started the American Indian department at Sotheby’s in the 1970’s, was at Indian Market with a contingent from the American Craft Museum.

“There isn’t really an art show for contemporary artists anywhere else where artists represent themselves with this kind of high quality,” said Holly Hotchner, director of the craft museum.

Major institutions like the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian and the British Museum, as well as regional ones like the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art, the Heard Museum, the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, and the Museum of New Mexico’s Museum of Indian Arts and Culture all had representatives wandering the streets to meet with artists and survey new works.

The Peabody Essex Museum of Salem, Mass., however, was on a buying mission. Early Saturday morning, Dan Monroe, executive director, and John Grimes, curator of Native American art, purchased a bracelet by Jesse Monongye titled “Spiritual Hand.” Mr. Monongye, a Navajo, is a jeweler known for his inlay work; he has been showing at Indian Market for 30 years.

The bracelet features a gold hand that ends as an arrowhead, and has an array of inlaid coral and turquoise that includes a Navajo sun face that rotates, revealing an Australian opal on the reverse side, symbolizing a full moon. Mr. Monongye’s work is in the collections of several museums, including the Heard and the Cooper-Hewitt.

“We’re looking for something that represents contemporary, more edgy, Native American jewelry,” Mr. Grimes said. It will join a collection of historic Indian art that dates back to the founding of the Peabody Essex Museum in 1799. Winning the best of market prize here has inaugurated many artists’ careers. Some past winners no longer show at the market, opting instead to display their work at galleries.

But Lonnie Vigil, 53, who won the top prize last year for a large water jar fashioned from micaceous clay that had been fired twice in a smothering process to create an iridescent gun-metal color, still shows up. He greets visitors at his booth along with many members of his family, including his mother, and his brother Larry, who assists him with production.

“I’m the person who creates it, but it’s Nambe Pueblo pottery,” Mr. Vigil said. “It belongs to my ancestors, my ancestry, to my family and to our community. Unlike Western art, we don’t claim the work as our own.”

While pottery and jewelry are the most prevalent art forms, textiles, beadwork, painting, sculpture and glass are also on display. A number of artists at Indian Market studied these crafts at the Institute of American Indian Arts here, including Tony Jojola, 44, who worked with glass at the school before going on to team up with Dale Chihuly.

Mr. Jojola’s work uses traditional Pueblo designs as a point of departure. Working with glass threads, he draws lightning, rain, clouds, spirit faces or water designs on glass forms that resemble pottery, ceremonial bowls, baskets or other vessels.

One of the highlights of Indian Market is seeing the large-scale collaborative work created each year for a benefit auction. This year the theme of the Indian Market live auction was “The Triumph of Indian Art,” because 12 Indian artists donated their time and art to create a sleek, and fully functional, Indian Art Car from a 1974 Triumph TR6.

Sam and Ethel Ballen, who own La Fonda hotel in Santa Fe, donated the car to benefit Indian arts groups. The souped-up model sold for $90,000. Dr. Elizabeth A. Sackler, president of the American Indian Ritual Object Repatriation Foundation, an organization that assists in the return of ceremonial materials, purchased the car.

Dan Namingha, 52, a painter and sculptor, who is both Tewa and Hopi, designed the custom paint job by blending Indian and American imagery, including numerous eagles painted on the sides and hood of the car. Other artists created a beaded steering-wheel cover and custom upholstery among other accessories.

“America has become a universal country, a melting pot of several cultures, and we’re under the blanket of that symbol of the eagle,” Mr. Namingha said. In the Hopi culture, eagles are a symbol of healing and are used in religious ceremonies.

The black-and-white checkerboard pattern on the sides of the car is also used on Hopi pottery to symbolize people, cloud formations or rain. The pattern also recalls the checkerboard flag used in automobile races, Mr. Namingha said. He also painted the four Hopi cardinal directions — red for south, blue for west, white for east, yellow for north — on the trunk of the car surrounding a spiral representing human migration.

Read original article, which appeared in Section B on p. 2.

© The New York Times Company